Updated on September 11th, 2025

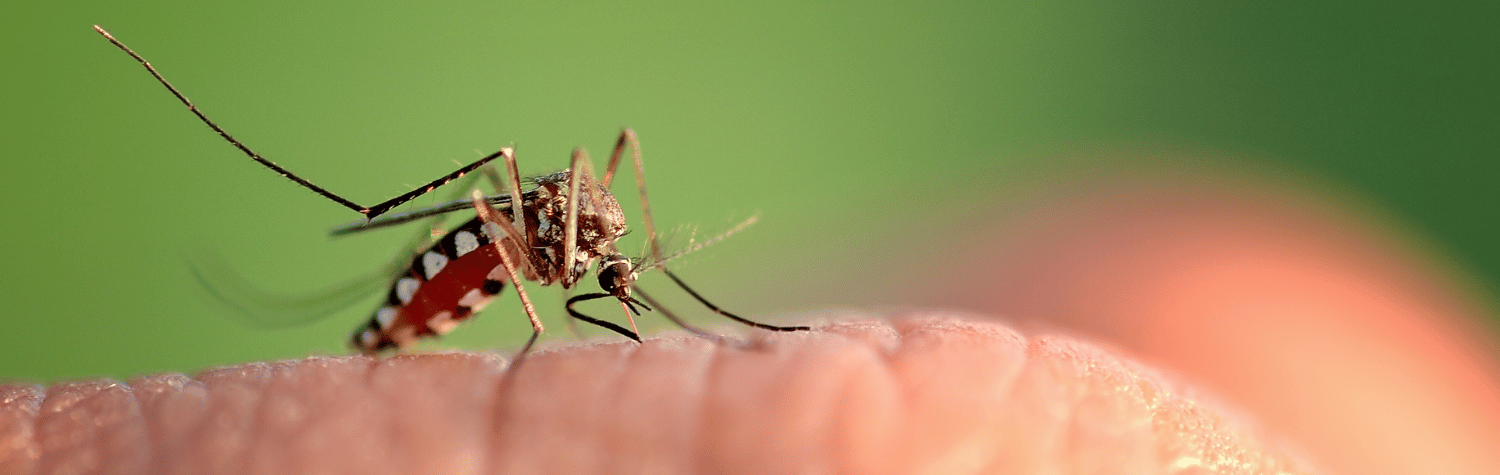

Mosquitoes are recognized as the most deadly insect in the world, responsible for more human deaths than any other creature. And some species—such as the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) and yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti)—transmit dangerous diseases.

By every measure—scale of impact, invasive spread and disease burden—mosquitoes secure their place at the very top of the list of deadly insects.

What is the deadliest insect in the world?

When people ask “What is the most dangerous insect in the world?” the contenders usually include the tsetse fly, the assassin bug and even the flea. The tsetse fly spreads sleeping sickness, a parasitic disease that can be fatal if untreated. Assassin bugs transmit Chagas disease, a chronic illness affecting millions in Latin America. And fleas carried the plague, which wiped out populations in Europe centuries ago.

Yet, none of these rivals the ongoing impact of mosquitoes. A United Nations biodiversity report notes that more than 37,000 alien species—including invasive mosquitoes—have been introduced worldwide, altering ecosystems and threatening public health. The Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) identifies invasive species—which includes mosquitoes—as one of the top five drivers of global biodiversity loss, alongside climate change and pollution.

Why mosquitoes are the deadliest insect on Earth

Mosquitoes harm humans. While other species—mentioned earlier—have historically caused severe illnesses, these threats are relatively localized and episodic. Mosquitoes, by contrast, transmit multiple pathogens globally—from dengue and Zika to chikungunya.

What makes mosquitoes so lethal? Their unmatched adaptability. They thrive in urban and rural environments, can exploit minimal water sources for breeding and respond quickly to climate shifts. And invasive species like the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) are continually expanding their range, amplifying disease transmission risks worldwide.

Globally, mosquito-borne illnesses claim over 700,000 lives annually, according to the World Health Organization—a figure no other insect comes close to matching.

Meet the deadliest mosquitoes: Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus

The yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) and the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) are among the most dangerous. Their flexibility allows them to colonize new regions, reproduce in water as small as a bottle cap and survive in both humid and dry climates.

Unlike many native mosquitoes that feed at dusk, these species bite aggressively during the day. Their eggs can also withstand dry conditions for months, hatching once water returns—making control especially difficult. These survival traits, combined with expanding ranges due to climate change, make containment a growing challenge.

Climate change is accelerating their spread. By 2050, research suggests these species could occupy habitats affecting nearly half the world’s population. In North America, Aedes aegypti is advancing north at roughly 150 miles per year, while Aedes albopictus spreads across Europe at about 93 miles per year.

Experts stress proactive measures. Moritz Kraemer, epidemiologist and climate-health researcher, notes: “If no action is taken to reduce the current rate at which the climate is warming, pockets of habitat will open up across many urban areas with vast amounts of individuals susceptible to infection.”

How mosquitoes spread deadly diseases

Mosquito-borne diseases pass through mosquito bites. Species including Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus carry viruses that cause dengue, Zika and chikungunya, while Anopheles mosquitoes transmit malaria.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 100–400 million dengue infections annually and more than 600,000 malaria deaths worldwide.

The clinical impacts vary by pathogen. Dengue can escalate to severe hemorrhagic disease and shock, especially in repeat infections. Zika is linked to congenital brain and neural defects when pregnant people are infected. Chikungunya often produces intense joint pain that can persist for months, and malaria remains a leading cause of child mortality in many regions. Each disease places different demands on hospitals and public health systems.

Mosquito-borne disease outbreaks depend on mosquito biology, environmental conditions and human activity. Climate change expands habitats, urban growth creates more breeding sites and global travel accelerates the movement of both vectors and viruses. These factors elevate local risk and can overwhelm healthcare systems, especially where resources are limited, according to WHO data.

During the 2015–2016 Zika outbreaks in the Americas, cases of congenital abnormalities surged, pushing health systems into emergency response mode (WHO).

The ecological threat of invasive species

The presence of invasive mosquitoes has a pervasive impact, disrupting local biodiversity and triggering cascading effects throughout ecosystems.

Biodiversity disruption

Invasive mosquitoes alter ecosystems by outcompeting native mosquito species for food and breeding habitats. Research published in The Rise of the Invasives and Decline of the Natives notes that invasive species can displace local populations, creating ripple effects throughout the food web. Native predators that rely on local mosquito species—such as birds, bats and fish—may lose a critical food source, weakening ecosystem balance.

Impacts on wildlife

When invasive mosquitoes dominate, they can also spread pathogens to animals, not just humans. Studies have linked their presence to increased disease risk in amphibians, birds and mammals.

Pesticide-heavy control measures

Managing invasive mosquitoes often relies on chemical pesticides. While effective in the short term, these treatments can harm non-target insects, including pollinators and natural predators. Residues may contaminate soil and waterways, raising concerns about long-term ecological health. This highlights the importance of plant-powered and eco-friendly mosquito control solutions that safeguard people, pets and the planet.

How to protect yourself and your community

Effective mosquito prevention starts with awareness and practical action. Eliminating standing water, installing window and door screens and planting natural repellents such as lavender, marigold or citronella can significantly reduce mosquito breeding and bites. Using safe, plant-powered mosquito control products can further protect your home and community. When traveling, stay informed on regional health advisories and follow recommended precautions to prevent spreading invasive mosquitoes.

Community involvement is equally important: participating in local clean-ups and supporting public health measures helps curb mosquito populations and protect vulnerable neighbors.

For a safe way to protect from mosquitoes, explore Dr. Killigan’s plant-powered pest control solutions—designed for families, pets and the planet. Together, informed individuals and eco-friendly strategies form a strong defense against the deadliest insect in the world.