Updated on October 22nd, 2024

Eliminating your bee problem can be a challenge.

First, it's crucial to accurately identify the type of bee you’re dealing with—and ensure it's actually a bee, not a stinging wasp. For instance:

- Leafcutter bees are extremely docile and rarely sting. Redirect their behavior (rather than attempt elimination).

- Honey bees are particularly sensitive to odors and abhor the smell of smoke. Remove them by lighting cardboard and twigs beneath their hive.

There are over 4,000 known bee species in North America alone, including:

- Carpenter bees

- Bumblebees

- Mason bees

- Long-horn bees

- Africanized honey bees

- Sweat bees

Identifying the bee species is essential because their presence and behavior can vary greatly depending on your region and environment, such as a country bungalow or a high-rise apartment. Your enjoyment of certain bee species, like I do, might also influence your approach.

My early encounter with a carpenter bee

My fascination with bees began early. I once held a male carpenter bee when I was seven years old and still remember that moment with vivid clarity...

Exhausted—with my arms and legs fully extended—I lay in my bright-yellow swim trunks near a river’s bank. The tall and lush grass enveloped me as I watched the water droplets on my forearms disappear while the sun had its way on them. The river had been cold—and invigorating. As I watched the wind sway the trees, a large bee landed on my bare arm. Its short legs tickled my goose-bumped skin. Its slow gait calmed my pulse. Its hair—yellow and black striped, and fuzzy and wild—seemed to spring up in joy. I wanted to pet this tiny creature and wondered if it had come for a drink. Was it attracted to the tiny pools of cool water on my skin? Then, it buzzed off.

I found that its presence had stirred my curiosity. I wanted to understand this unique creature.

What are carpenter bees? What is their life cycle?

Carpenter bees have black bodies, often with yellow hairs on their head and thorax. They are solitary bees that burrow into dead wood. They tend to be non-aggressive, peaceful fliers that mate once and for life. They do not produce honey, as they’re not a honey-producing family.

Note: Less than 5% of bee species make honey.

In the spring, carpenter bees emerge from their wooden dwellings, which can come as early as February (in the southern states) and as late as the end of May (in the northern states). The carpenter bees then gather food and begin the search for their life partners.

Once hitched, the newly knotted pair make preparations for the near future—the female as a homebuilder and the male as the home’s protector. Once their eggs are safely laid, the parents see their life assignment as completed and die.

The next generation emerges in late summer—during the months of August and September—growing, pollinating and then settling in for the winter. Those that survive—as only a percentage make it through the colder temperatures on limited pollen that was stored up—are seen in the spring.

Do carpenter bees pollinate?

Like other bees, carpenter bees are master pollinators. They use their powerful thoracic muscles to produce strong vibrations that forcibly expel dry pollen grains out from inside the flower's anthers—the part of a flower where pollen is produced. This pollen then sticks (and falls from) their fuzzy bodies, thus pollinating other vegetation, including eggplant and tomatoes. This type of gathering is called "buzz pollination."

Additionally, while carpenter bees are solitary, their activities have a significant cumulative effect on the environment. They are particularly vital for the pollination of open-faced flowers—such as sunflowers and azaleas—and contribute to the diversity of plant life by transferring pollen between plants that are not visited by other bee species.

Fun fact: Unlike honey bees, carpenter bees tend to be less efficient in transferring pollen between flowers, but they compensate by visiting a variety of plants, which helps maintain plant genetic diversity.

What is the difference between carpenter bees and bumblebees?

While it can be difficult to tell the difference between carpenter bees and bumblebees, there are a few physical attributes that help you differentiate these two varieties.

Carpenter bees:

- Abdomen: Exhibits a shiny, smooth and hairless surface, reflecting a more polished appearance compared to bumblebees.

- Size: Generally larger, typically measuring around one to one-and-a-half inches in length, which makes them more robust and noticeable in the garden.

- Nesting habits: Known for their unique behavior of boring into wood to create nesting sites, which can lead to noticeable damage to wooden structures.

- Social structure: Solitary by nature; each adult bee overwinters individually, often in old tunnels or under eaves, without a colony's support.

Bumblebees:

- Abdomen: Covered in a dense layer of hairs, typically featuring striking black and yellow bands, giving them a fuzzy appearance.

- Size: Smaller in comparison, usually ranging from one-half to one inch, which makes their presence less imposing.

- Nesting habits: Prefer to nest in pre-existing cavities below ground—such as abandoned burrows—which makes them less disruptive to human habitation.

- Social structure: Highly social and live in colonies, which can include a few hundred bees.

Do carpenter bees sting?

Male carpenter bees do not have stingers. Accordingly, if you notice this species buzzing around your home, there’s no need to fear being stung. The male is simply fulfilling his duties.

Tasked with protecting his female’s nest from other (flying) insects, the male will hover and dive-bomb in front of any threat near his female’s nesting site, hoping that his size and skill will ward off the challenger.

On the other hand, the female carpenter bee has a stinger. Thankfully, she is usually quite preoccupied with constructing the perfect tunnel for the tiny little eggs that she will lay and won’t mind your presence. The females seldom sting. When she decides to attack, though—which is usually only when she was handled or provoked by people—her sting packs a wallop.

How did carpenter bees get their name?

Carpenter bees are named for their infamous activity of boring holes into wood. With her powerful mandibles (teeth), the female bites her way through soft wood to create tunnels for laying eggs. Carpenter bees prefer unpainted, weathered or rotting wood, especially less dense varieties such as redwood, pine, cypress and cedar. The entrance hole that the female creates is perfectly round and about the diameter of your little finger.

As they excavate, carpenter bees meticulously discard the chewed wood outside their nests, which can often be seen as small piles of sawdust beneath entry holes.

Fun fact: Their nesting habits can help aerate and recycle dead wood.

Where do carpenter bees nest?

Around your house’s property and closer to home, carpenter bees will cause damage. These are their most common nesting sites:

- Decks

- Outdoor furniture

- Fence posts

- Swing sets

- Porch ceilings

- Eaves

- Fascia boards

- Rafters

- Window trim

- Siding

- Wooden roof shakes

They prefer to nest in locations where the roof overhangs, as they do not want their tunnels to get flooded with rain or filled with debris. They also don’t want to be seen by birds. Unfortunately, they don’t always have the same fear of humans and will gladly choose locations both in deck joists and in patio furniture.

They will nest in pre-existing bee homes. Carpenter bees have a phenomenal sense of smell. The female will follow the pheromone trail of a deceased carpenter bee, locate her once-occupied abode and gleefully take up residence there. Occupying an already-established home is far less work and provides more immediate shelter, (though the female will probably do a bit of remodeling first).

How do I get rid of carpenter bees instantly?

From late fall until very early spring, carpenter bees are still hibernating or have passed away in their tunnels. Winter is the time to kill bees fast.

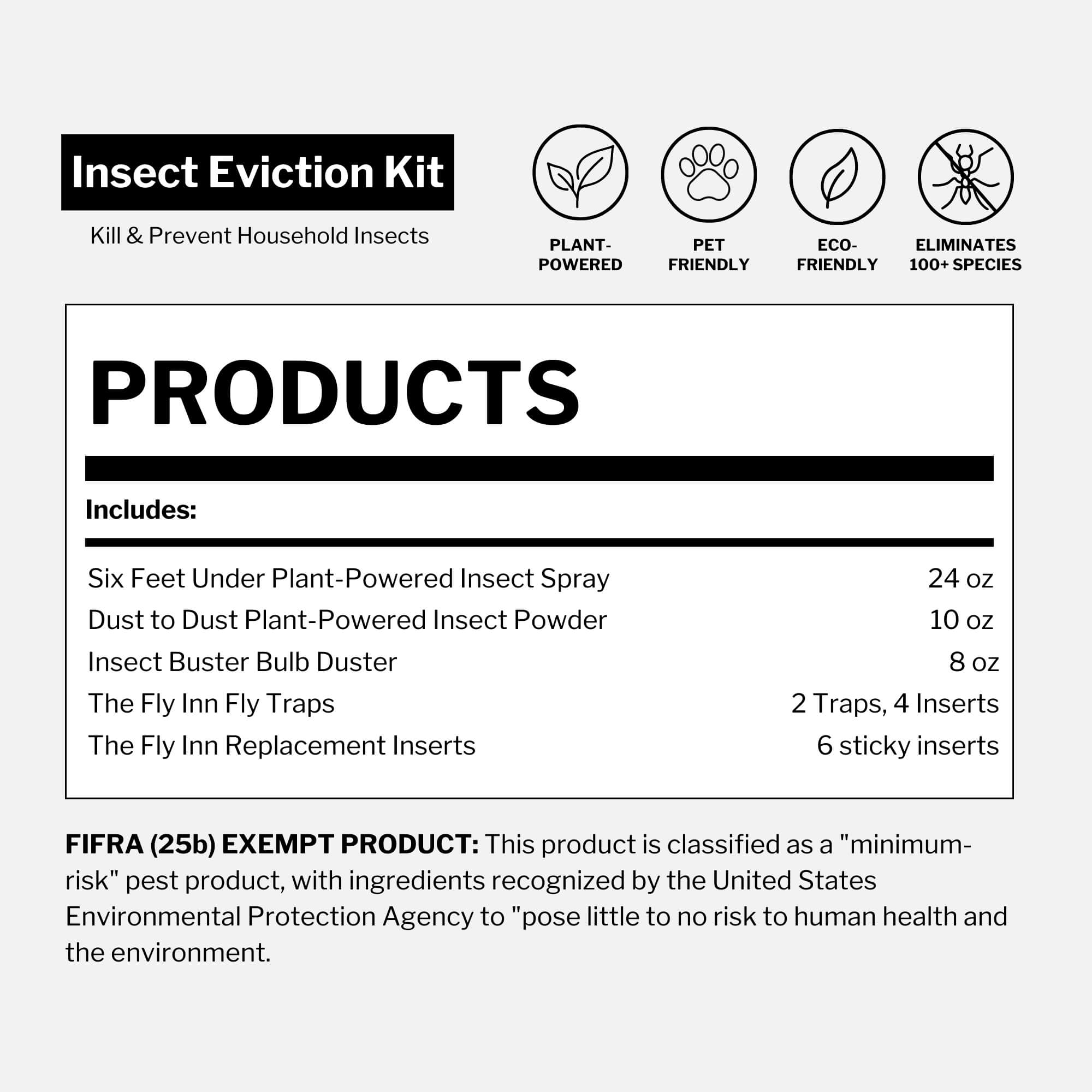

- Disperse a non-toxic pest control powder. Using the Insect Buster Bulb Duster, attach the vinyl tube to the brass curved tip. Push this tube into the bee’s hole and give the Insect Buster a good squeeze. By dispersing diatomaceous earth (DE) into the hole, you’re ensuring that the adult carpenter bees will pass—if not already deceased—as well as the spring-awakening larvae, as both will have to walk through the DE as they attempt to exit the premises. Once covered with this powder, there’s no longer any hope for survival, as DE's tiny dust particles will cling to the legs and bodies of the bees and poison them as they attempt to groom the powder off.

- Fill pre-existing holes. Using a one-half inch diameter wooden dowel, cut it into smaller sections, cover the end section with wood glue and push it into the hole. Saw off the extra length so that the dowel is flush with the wood. Once dry, paint over this area. This will prevent carpenter bees that are scouting for a new home to consider these locations. Note: Because DE does not kill bees on contact, I advise waiting 24-48 hours before filling the pre-existing holes.

- Monitor bee activity. Once the nests are filled and secure, remember those locations for the spring. They clearly made great homes for carpenter bee nests. In late winter, consider dispersing DE around pre-existing, filled holes, remembering that carpenter bees will return to the same place year after year. For the homeowner this means that, without proactive measures, you could see them again this spring.